January 1, 2025

2024-It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a year consumed by trying to repair and restore things that fell apart or were destroyed, balanced out by the daily wonder of our new grandson River Henry.

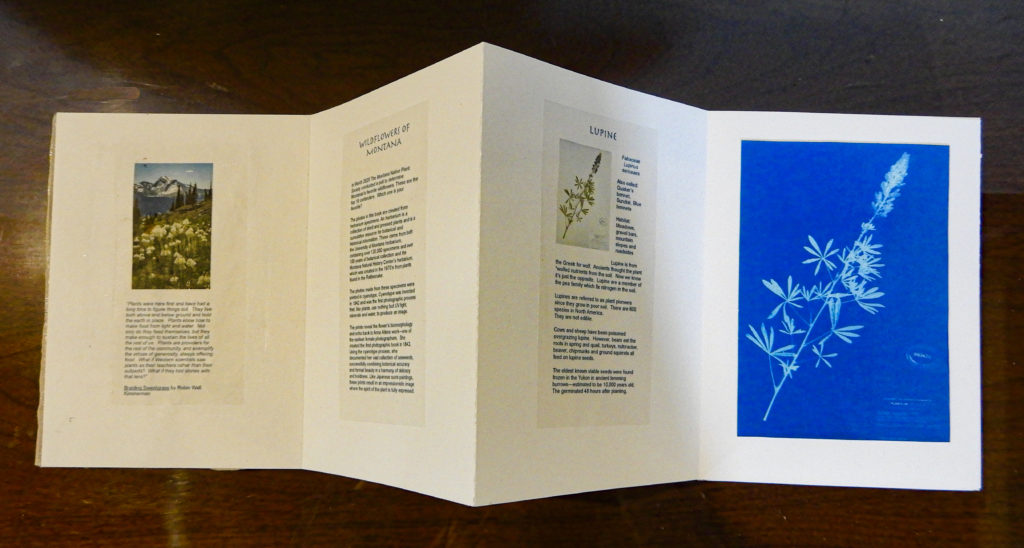

I swore I would never be one of “those” grandmothers—but I find myself plying everyone with pictures of this amazing child and the two or three days a week I get to babysit are the highlight of my life. He has reignited my sense of curiosity, where something as ordinary as a pine needle suddenly becomes a thing of fascination and surprise.

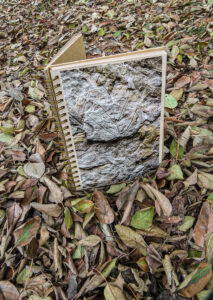

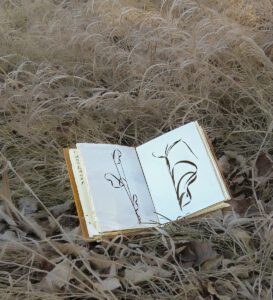

He reminds me to use all my senses. As a photographer I have become too habituated to focusing on the visual. He prompts me to explore the tastes, sounds, smells and textures of everything we encounter, deepening my experience a hundredfold. And the best part—I don’t have to deal with the lack of sleep his poor parents do. He has been the thing that keeps me looking forward to the future and reiterates my commitment to being a good ancestor, not just for him, but for the planet.

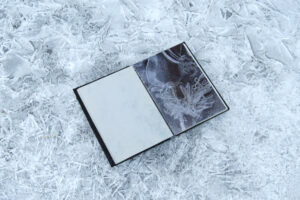

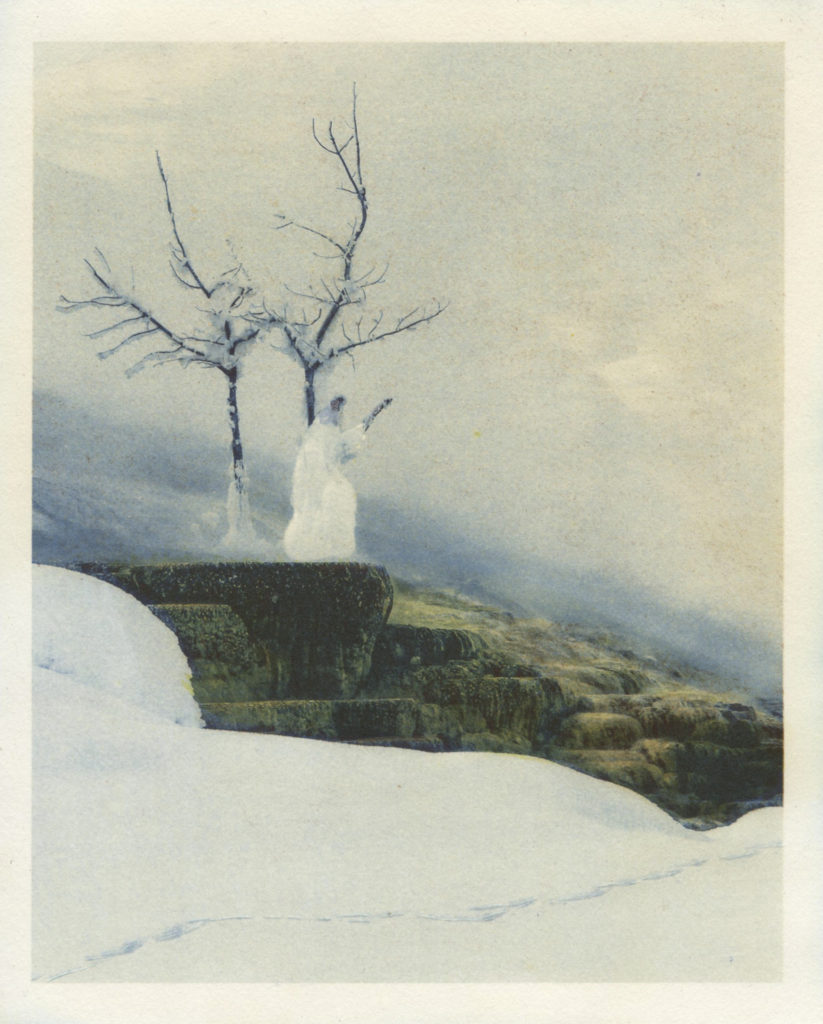

It comes at a time when the effects of our changing climate could not be denied as we dealt with a nearly snowless winter—the first year since I was 2 years old I did not ski; a summer of long stretches of heat over 100 degrees and draught; a fire that threatened the homestead cabin; and then, in July a catastrophic derecho—hurricane force winds that tore through the Missoula valley and decimated the backwoods. A hundred trees, uprooted or broken, the treehouse smashed, the pond covered by fallen cottonwoods, four trees on one of our outbuildings, the chicken coop crushed, and a massive cleanup job that continues into the new year.

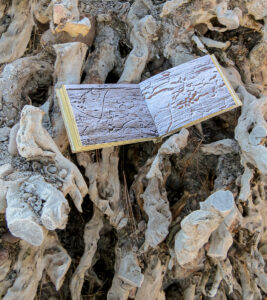

The backwoods are forever changed. The four elder ponderosas that greeted me each morning on my walk are uprooted, the pond is inaccessible, the heron rookery destroyed. The osprey nest was blown off the the platform just days before the chicks would have fledged and they were killed. The mother osprey stood perched on the platform for weeks, as if unable to process what had happened. For months afterwards the woods were quiet, it was if everything fled the tangled downfall and broken branches. A slew of lights now penetrate the refuge of the woods and I feel newly exposed and unable to ignore the influx of new housing developments as the city spreads out consuming the rural ranch and farmlands around Missoula.

Right now I feel the loss and destruction. The backwoods feel ruined. But I remember when the Red Bench fire ripped through Glacier’s North Fork valley in 1988. How I watched as the place that was so sacred to me burned and cut us off from Kintla Lake where we were spending summers as backcountry rangers. It too felt ruined. But then I marveled as the fireweed flamed up from the burnt earth and the woodpeckers flocked to the blackened snags The serotinous cones burst and spread their seeds in the ash and soon there were bright green saplings covering the forest floor. The rusted pine beetle killed trees that clogged the landscape before the fire were replaced by a vibrant healthy forest.

I know when River and I begin exploring the backwoods again I will find new things I have overlooked before, that familiarity has blinded me to in the past. The backwoods will once again become a place of refuge and discovery. Grandmother cottonwood, who proudly presided over both of my sons’ weddings still stands. And the broken snags will provide nest sites for flickers and chickadees and many others. The deadfall cottonwoods will sprout with mushrooms and rabbits will find refuge from the hawks in the tangled branches. I don’t know if the herons or osprey will return, but the great horned owls are calling to each other every night, and with luck there will be another generation born in the woods. It will still be a place to explore, to discover plants and tracks and feathers and bones, to build forts in the bushes and to collect worry rocks and wishing rocks.