The morning after the election was a heartbreaking, confusing time for me. It was not just that my candidate had lost–that had happened before–or that the president elect would not agree with me on the issues that I consider most important. It was not even the possibility that this man might lead the country into another catastrophic war. That too had happened before. No–what devastated me was the fact that I could not understand how the electorate could vote for someone who so clearly had no moral or ethical center. Did that mean that half the country also lacks a moral and ethical center?

The morning after the election was a heartbreaking, confusing time for me. It was not just that my candidate had lost–that had happened before–or that the president elect would not agree with me on the issues that I consider most important. It was not even the possibility that this man might lead the country into another catastrophic war. That too had happened before. No–what devastated me was the fact that I could not understand how the electorate could vote for someone who so clearly had no moral or ethical center. Did that mean that half the country also lacks a moral and ethical center?

Needing some way to wrap my mind around this post-truth, post-values world, I turned to one of my favorite poems–one that has given me solace in the past during troubled times.

The Peace of Wild Things

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

© Wendell Berry. This poem is excerpted from “The Selected Poems of Wendell Berry”

I headed out to the pond in the backwoods. Seating myself under the great cottonwood, I stared up into its now bare branches. The red-tail hawk, who had raised a chick in the massive nest over my head was circling high in the sky , scanning the world below. His shrieking kee-ree sounded like the cry my heart was making. Because this time, I didn’t feel the peace of wild things. I felt fear. Fear for the wild things of which I am an integral part.

It was an unseasonably warm November day, after an unseasonably warm October, after the warmest year on record–again. The mountains were still bare of snow. The aspen trees, just weeks after loosing their autumn leaves were beginning to bud out, the furry white tips of the catkins emerging from their brown winter casings. What would happen when the frost finally did come? The pond was shrunk down, leaving a bathtub ring of decaying leaves on its shore. Through the silvery trunks of the cottonwoods I could see the reddened pine needles of another beetle-killed ponderosa, Our warmer winters are a boon for the pine bark beetles who are decimating our western forests and have created a fifth season–fire season, when massive forest fires eat millions of acres every year.

I thought about our next president for whom reality is a TV show, thought about him sitting in his gilded Trump tower and wondered if he was so cut off from the natural world that he couldn’t see what was happening–that he could really believe that Climate Change was a Chinese hoax, not the gravest threat to our future and the most pressing and dangerous issue. This was not a problem you could wall out.

I thought about the people who voted for him. I knew several people who were “unfriending” anyone who had supported Trump. But I realized that reacting from fear, anger and hate was exactly what his supporters had done. They saw the problems in the world–terrorism and an economy that was all about the bottom line and not about the workers, where everyone was nothing more than a consumer and their way of life was threatened by so many global issues too complex to understand–they saw those problems as overwhelming and unsolvable. And it made the them afraid. Trump told them that he could solve those problems. And they wanted so badly for someone to step up and do just that that they gave him their votes–and their futures.

What I realized was that they weren’t that much different from me. I too saw the problems in the world–most particularly Climate Change as overwhelming and unsolvable and I felt defenseless in the face of global powers who were refusing to confront the reality of the situation. I have let myself get distracted by other things, I have stopped paying the deep attention that is necessary for any relationship, and that includes my relationship with the natural world. And so I have sat back and waited for someone else to fix it. I need to react, not out of fear, but out of my own moral center.

From Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril: page 469

“The times call for integrity, which is the consistency of belief and action. The times call for the courage to refute our own bad arguments and call ourselves on our own bad faith. We are called to live lives we believe in–even if a life of integrity is very different, let us suppose radically different from how we live now. Knowledge imposes responsibility. Knowledge of a coming threat requires action to avert it. There is no way around it, if our lives are to be worthy of our view of ourselves as moral beings. How to begin? Maybe with four lists. List 1: These are the things I value most in my life…List 2: These are the things I do that are supportive of those values. List 3: These are the things I do that are destructive of those values. List 4: These are the things I am going to do differently. From now on. No matter what.”

List 1: A healthy, life affirming relationship with the natural world.

List 2: I can begin by paying attention. By speaking out in defense of what I love. Recommitting to this blog is part of that. Supporting those who are working to change the way we relate to the natural world is another.

List 3: Waiting for someone else to solve the problems while I remain quiet and afraid is destructive to my values and ultimately to my spirit.

List 4: This is a start. I will recommit to the things I already do, like trying my best to eat locally, to be conscious of how my decisions affect the rest of my community and the world, to an ethical relationship to money and how my spending and my investments support or hurt the natural world. But this is only a start. One person may not make a difference in the bigger picture, but “each of us, right now, at this exact moment in time, has the power to choose to live the moral life, to live a life that is indeed worth living.” Michael P. Nelson

Like this:

Like Loading...

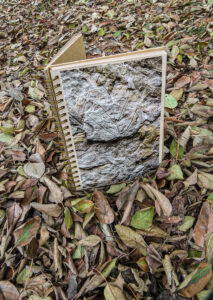

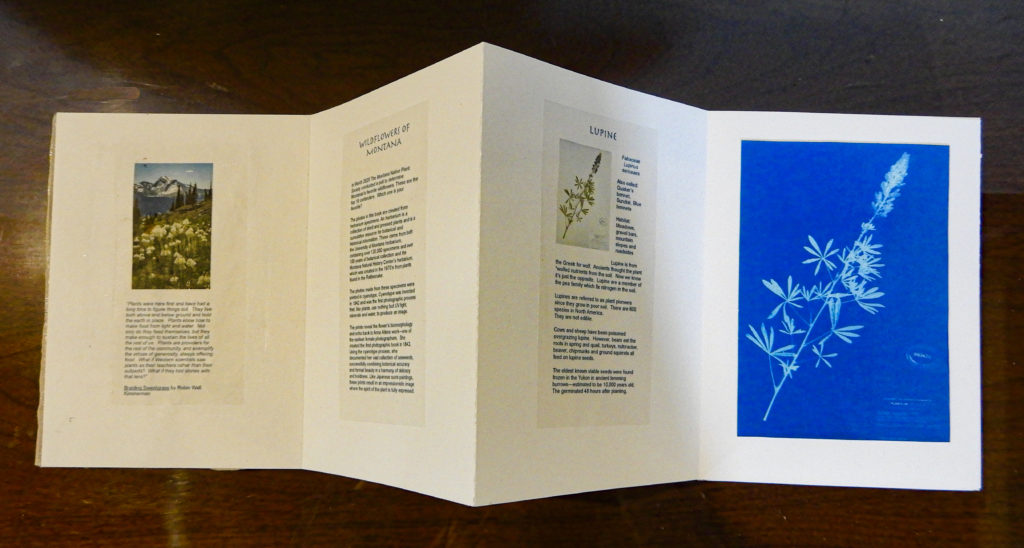

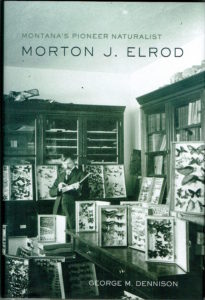

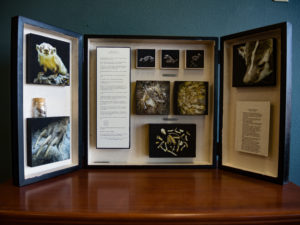

Wunderkammer (Cabinet of Wonders)

Wunderkammer (Cabinet of Wonders) Articulating a Story

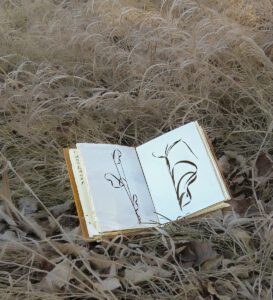

Articulating a Story Haunted by Owls

Haunted by Owls Swan Song

Swan Song The morning after the election was a heartbreaking, confusing time for me. It was not just that my candidate had lost–that had happened before–or that the president elect would not agree with me on the issues that I consider most important. It was not even the possibility that this man might lead the country into another catastrophic war. That too had happened before. No–what devastated me was the fact that I could not understand how the electorate could vote for someone who so clearly had no moral or ethical center. Did that mean that half the country also lacks a moral and ethical center?

The morning after the election was a heartbreaking, confusing time for me. It was not just that my candidate had lost–that had happened before–or that the president elect would not agree with me on the issues that I consider most important. It was not even the possibility that this man might lead the country into another catastrophic war. That too had happened before. No–what devastated me was the fact that I could not understand how the electorate could vote for someone who so clearly had no moral or ethical center. Did that mean that half the country also lacks a moral and ethical center?