Forest fire smoke

the Ponderosa, thinking tree

contemplates its breath

Today, while my husband prepares for his annual hunting trip, I am up at the homestead gathering. As convenient as my garden is, right out my front door with its neat rows of produce ready for the picking, its domesticated flavors can’t compare to the wild tanginess of a berry foraged from the forest. Half the experience of eating a huckleberry or spreading thimbleberry jelly over your toast is the memory of finding it–the day spent in the mountains taking careful notice of things, discovering not only the berries you were seeking, but stumbling upon the carefully built midden an industrious chipmunk has gathered against the winter snow.

Today, while my husband prepares for his annual hunting trip, I am up at the homestead gathering. As convenient as my garden is, right out my front door with its neat rows of produce ready for the picking, its domesticated flavors can’t compare to the wild tanginess of a berry foraged from the forest. Half the experience of eating a huckleberry or spreading thimbleberry jelly over your toast is the memory of finding it–the day spent in the mountains taking careful notice of things, discovering not only the berries you were seeking, but stumbling upon the carefully built midden an industrious chipmunk has gathered against the winter snow.

I read recently that women are better suited to gathering than men. It seems that we see colors more vividly than the guys and I wonder then, what the world looks like through their eyes, slightly less saturated, a bit duller perhaps.

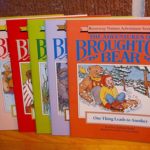

Anyway, on this fine summer day I am gathering rosehips to dry in the sun–a winter’s bounty of vitamin C rich tea. And of course, a few kept by to make a rose hip cake. When the boys were little and we spent our summers rangering in Glacier Park, their favorite stories were the Broughton Bear books, by Susan Atkinson-Keen. The main character was a little boy who lived in a cabin in the wild, just like my sons. And the boy in the stories lived with a grandfatherly bear who took him out in the woods to share some natural history and gathering adventure which always ended in the preparation of food, recipe included. Thus began our tradition of gathering the fat red rosehips to make a summer rich treat in the middle of winter.

Anyway, on this fine summer day I am gathering rosehips to dry in the sun–a winter’s bounty of vitamin C rich tea. And of course, a few kept by to make a rose hip cake. When the boys were little and we spent our summers rangering in Glacier Park, their favorite stories were the Broughton Bear books, by Susan Atkinson-Keen. The main character was a little boy who lived in a cabin in the wild, just like my sons. And the boy in the stories lived with a grandfatherly bear who took him out in the woods to share some natural history and gathering adventure which always ended in the preparation of food, recipe included. Thus began our tradition of gathering the fat red rosehips to make a summer rich treat in the middle of winter.

ROSE HIP CAKE

2 cups dried rose hips

1 cup water

blob of butter

2 eggs

1 cup sugar

1 cup flour

1 tsp. baking powder

Cover and simmer rose hips in water for 20 minutes. Strain to remove seeds, hairs, and pulp. Set aside 1/2 cup of this juice with a blob of butter.

Beat eggs in large bowl. Beat in sugar. Add flour, baking poweder, and hip juice. Mix well. Pour into greased 8″x8″ pan and bake 25 minutes at 350 degrees. Remove from oven.

Topping

3 tbls. butter

3 tbls. brown sugar

2 tbls. cream

1/2 cup sliced almonds

Mix topping in small pot and heat until butter melts. Pour over cake, then brown slightly under the broiler.

Enjoy!

Crossing the glacial moraine that dams Racetrack Lake above Deerlodge, we make our way to the trailhead at the lake’s inlet. We are soon ascending through a hummucky, rock strewn forest of lodgepole pines. Sticks and stones won’t break our bones as we make our careful way up the trail, but climbing over deadfall and around the boulders will surely make our bones ache tomorrow morning. We are traveling through a forest of erratics–rocks resting far from the source, carried from the high peaks with their sharp ridges on a sheet of glacial ice and left behind as the ice age ended.

Crossing the glacial moraine that dams Racetrack Lake above Deerlodge, we make our way to the trailhead at the lake’s inlet. We are soon ascending through a hummucky, rock strewn forest of lodgepole pines. Sticks and stones won’t break our bones as we make our careful way up the trail, but climbing over deadfall and around the boulders will surely make our bones ache tomorrow morning. We are traveling through a forest of erratics–rocks resting far from the source, carried from the high peaks with their sharp ridges on a sheet of glacial ice and left behind as the ice age ended.

We too are a group of erratics, most of us from other places, brought here by jobs or dreams of living just a bit closer to the bedrock, seeking out a place where we might be surrounded by space and wildness rather than the press of other people and commerce. Only two or three of us grew up in the surrounding valleys and their stories of those ranching years and their knowledge of the flowers and birds helps ground the rest of us to our chosen homeland.

We think of rocks as steadfast and immovable, but each of these giant boulders is a monument to change. Born in a liquid fire, they were expelled from the earth’s crust by a force of unfathomable power, cooling slowly over time, then squeezed and crushed and molded by tremendous pressures, thrust up in the violent collision of tectonic plates and rising thousands of feet into the sky. Then they were sheared from their mother mountain by rains and freezes and broken by tons of glacial ice, scraping and filing their rough edges as they were carried down the mountain on the glacier’s back. Even when the ice melted and these erratics came to rest in what would, aeons on become a forest, their stories did not end. The seeds and spores of lichen and moss were brought by the wind from far-off places and began the slow process of burrowing down into the rock’s skin, breaking it apart, creating pockets of loose soil where grasses and then small bushes could get a foothold, maybe even a tree might reach its root tentacles down into cracks and crevices, feeding on the essence of the boulder.

“Stone is the face of patience,” Mary Oliver says. Yes, these erratics are the face of patience, but their story is one of constant change, being shaped by powerful forces, no will of their own, no clinging to any one state, no concept of being a part of something bigger or broken apart from that, no sense of being a separate thing, no self. Only a patient yielding to impermanence. How can we imagine such a thing?

“Stone is the face of patience,” Mary Oliver says. Yes, these erratics are the face of patience, but their story is one of constant change, being shaped by powerful forces, no will of their own, no clinging to any one state, no concept of being a part of something bigger or broken apart from that, no sense of being a separate thing, no self. Only a patient yielding to impermanence. How can we imagine such a thing?

I am not a good fisherman. I would far prefer to sit on the bank reading a book about other people’s catches than stand patient in the icy cold water casting out again and again, getting frustrated by lines that fall heavily on the surface rather than sailing out in perfect arcs to land lightly in the still pool where the biggest lunkers lie. My fly gets caught up in bushes behind me as I try to cast forward and I spend an hour untangling the line from the willows of memory, rather than simply cutting it off and tying on another fly. I stumble on the slippery rocks of questions I don’t have the answers to and find my waders filling up with the water of confusion, weighing me down. Or my fly drifts away and gets tangled in the snag that washed up on the bank in last year’s flood of life experience.

I am not a good fisherman. I would far prefer to sit on the bank reading a book about other people’s catches than stand patient in the icy cold water casting out again and again, getting frustrated by lines that fall heavily on the surface rather than sailing out in perfect arcs to land lightly in the still pool where the biggest lunkers lie. My fly gets caught up in bushes behind me as I try to cast forward and I spend an hour untangling the line from the willows of memory, rather than simply cutting it off and tying on another fly. I stumble on the slippery rocks of questions I don’t have the answers to and find my waders filling up with the water of confusion, weighing me down. Or my fly drifts away and gets tangled in the snag that washed up on the bank in last year’s flood of life experience.

Don’t get me wrong–I get plenty of nibbles. Fish do rise to the surface and bite my fly. But I have such trouble setting the hook. I catch a glimpse of the silvery flash of scales–the rainbow colors of insight, but then they wiggle off the hook and slither away downstream, my line lying slack on the water’s surface. I am tempted to give up this silly sport. It is such a cliche anyway–a Montanan angling for fish and words. And yet…

Bench snuggled into the shade of the Ponderosas. Looking out beyond the meadow to the mountain range across the valley. Openness, spaciousness, while feeling nested. I have always wanted a mountain view, always loved the aerial sense it gives me of my place in the world. A living topographic map laid out before me. My mind can wander those far off ridge lines–imagine itself climbing up the scree slopes of Petty Peak. It can dip down into the parked out forests of Ponderosa pine on the near slopes. Mounds of gravelly sand that once were beaches on Glacial Lake Missoula. My mind can conjure its watery surface creeping up the sides of the valley, shaping sand bars and inlets as it rose and fell over eons.

Bench snuggled into the shade of the Ponderosas. Looking out beyond the meadow to the mountain range across the valley. Openness, spaciousness, while feeling nested. I have always wanted a mountain view, always loved the aerial sense it gives me of my place in the world. A living topographic map laid out before me. My mind can wander those far off ridge lines–imagine itself climbing up the scree slopes of Petty Peak. It can dip down into the parked out forests of Ponderosa pine on the near slopes. Mounds of gravelly sand that once were beaches on Glacial Lake Missoula. My mind can conjure its watery surface creeping up the sides of the valley, shaping sand bars and inlets as it rose and fell over eons.

Or my mind can creep in closer, dancing in the meadow with the waving wands of fuzzy grasses. It can peer through the bushes and see Grandmother Rhubarb–imagining her steadfast presence in this place for a hundred years–planted by a woman long dead and not a native to these mountains. But the rhubarb still flourishes here, reminding me of the first family to sit on this hillside and look out at a sunset coloring up the view.

Maybe my mind doesn’t even leave this bench. A piece of pine, sawed and shaped by the hands of a young man in Oregon, never imagining its place in the Montana mountains and the two women who would sit and write here, spurred on by their experience in his homeplace weeks before.

This is a special place where the mind has the freedom to wander back and forth in time and in and out of different perspectives. To be a butterfly tossed about on the breeze, giving itself up to the gusts and riding the waves of grass. Or smelling the breeze like my dog–nose into the wind to catch scent of whatever might be lurking unseen in the woods.

What have I missed at the Homestead today while I have busily picked away at my to-do list? What egg hatched today, what track was left in the soft mud as a sign of the community I still sit on the periphery of? What new flower bloomed that I need to learn? What berry was set?

What have I missed at the Homestead today while I have busily picked away at my to-do list? What egg hatched today, what track was left in the soft mud as a sign of the community I still sit on the periphery of? What new flower bloomed that I need to learn? What berry was set?

So much happens each day in the woods and the fact that I am not there to witness it leaves me with a deep feeling of loss, even if I don’t know what it is I am missing. When I go for hike up at the Homestead and see the round leaved orchids blooming it is like stumbling across a hidden treasure and I greedily want more. I want lupine and larkspur to tumble down the hillsides like a blue steam of water. I want to say I was there when the ravens fledged from the nests, that I saw the eagle teaching its young to fly. It breaks my heart knowing that a bear might be crossing the meadow and all I will have of his passing is pile of dried scat. It makes me ache to think that a bobcat might be stalking a snow shoe hare in the tangle of brush by the old cabin and I will go to my grave never having seen a bobcat in the wild.

No matter how many round leaved orchids or mountain lion tracks I find, I will always wonder what I missed. What I missed paying bills or grocery shopping or doing laundry or even being off somewhere else entirely, on a trip to experience other wonders. I even ache for the week I was in the Big Horns seeing alpine fields of scarlet geraniums and a moose and her baby in the Lamar Valley. Because something equally miraculous was happening at the Homestead and I missed it.