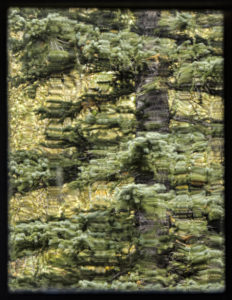

Whatever lies beyond

looses it’s coherent shape

blurred through Covid’s lens

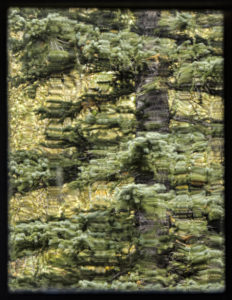

Whatever lies beyond

looses it’s coherent shape

blurred through Covid’s lens

The stay at home order has been lifted, bars and restaurants opening up, retail and soon the farmer’s market, though all with restrictions. Life is slowly getting back to some form of “normal”. But I am not eager to get back into the flow of things, to end this quiet time of introspection and solitude. The first few weeks I could not focus on anything, kept scrolling social media, and the newsfeed. But I could not bear the way everything is flung out–anger and outrage and that terrible need to find someone to blame for what is happening. At first I felt the need to “stay informed” but then I realized it didn’t really matter if I knew what so-and-so said, how someone reacted–what I really needed was some perspective.

Finally, I learned to put down the phone, turn off the computer and stand still and listen. Taking me out of the human community encouraged me to connect to the natural community. I had the time and space to really feel spring awakening the woods, to go barefoot in the greening grass, to make a daily trip to the pond instead of to town, to listen to the gossip of the ducks and geese, the raucous chatter of the redwing blackbirds and flickers, to watch the drama of the osprey’s return and discovery of a goose in their nest. I looked forward to the daily visit of Woody the Woodpecker and his silly laugh. And was awed when a sharp shined hawk took down a dove just outside my kitchen window.

This has also been a time for reading–my favorite kind of reading–quiet, introspective books that encourage deep thought. Because that is what seems to be lacking in this crisis. Deep thought rather than instantaneous reaction. Reading writers like Wendell Berry. Scott Russell Sanders and Matthew Crawford’s The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction, gave me chance to put all of this into a social context. I could see someone’s deep, considered thought processes, analyzing a problem and understanding all the intricacies and issues that are involved, then filtering all of it through direct experience and feeling.

Of late I have returned to Gift From the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Written more than 50 years ago, it has much to say about this time of isolation. It’s the story of her weeks alone at the beach and how the solitude and time out of time gave her the opportunity to reflect on all the different seasons and responsibilities of a woman’ life. Though times have changed, her deep insights and perspectives still have resonance. And near the end she echoes my fears for how I will respond as this stay-at-home order expires:

“When I go back will I be submerged again, not only by centrifugal activities, but by too many centripetal ones? Not only by distraction, but by too many opportunities? Not only by dull people but by too many interesting ones? The multiplicity of the world will crowd in on me again with its false sense of values. Values weighed in quantity, not quality, in speed, not stillness, in noise, not silence, in words, not in thoughts, in acquisitiveness, not beauty. How shall I resist the onslaught?”

How indeed.

with spring’s arrival

unexpected snow flurries

swirling in blue skies

In 2018 Rebecca Solnit wrote a piece for Orion Magazine and foresaw this:”We are going to have to stay home a lot more in the future. For us that’s about giving things up. But the situation looks quite different from the other side of all our divides …From outer space, the privileged of this world must look like ants in an anthill that’s been stirred with a stick: everyone constantly rushing around in cars and planes for work and pleasure, for meetings, jobs, conferences, vacations, and more. This is bad for the planet, but it’s not so good for us either. Most of the people I know regard with bemusement or even chagrin the harried, scattered lives they lead. For the privileged, the pleasure of staying home means being reunited with, or finally getting to know, or finally settling down to make the beloved place that home can and should be, and it means getting out of the limbo of nowheres that transnational corporate products and their natural habitats — malls, chains, airports, asphalt wastelands — occupy. It means reclaiming home as a rhythmic, coherent kind of time. The word radical comes from the Latin word for root. Perhaps the most radical thing you can do in our time is to start turning over the soil, loosening it up for the crops to settle in, and then stay home to tend them.”

I read this back in 2018 and had forgotten about how much it resonated with what I was trying to build for myself here at home. But of course I’m one of the privileged. I think of the refuges in war-torn countries, families that have had to leave their homes because of gang violence, communities and cultures that have been uprooted by extractive industries that feed the privileged’s lifestyle. It’s time for all of us to reflect on what this enforced home sequestration has revealed to us about the ways we might change our attitude towards home, towards our lifestyles, what we really do need and ways we might take back our responsibility to change the impacts we have on the earth and on each other.

Franticly busy

gnawing away at our work

only to get hung up

Danger! Beware of the Rocks! One of the most obvious rules of boating. Especially the rocks near the shore, barely visible above the water or just beneath the surface—unseen until you are right up on the them. But there are times when, despite your best navigational efforts, a sudden fierce gust of wind hits your small vessel and sends it smashing into those very rocks. A crack in the side of your boat, or worse yet, a bent propeller that leaves you stranded.

We have been blown up onto the rocks by this pandemic. They have not only broken our society wide open, we find ourselves hopelessly grounded. It’s easy to let the fear drown us, despite all our efforts to bale ourselves out. This is not time to focus on whether or not someone should have seen this coming, should have been paying better attention. We are stuck in this crisis. The water is rushing in faster than we can bale.

What to do? This morning I read a really thoughtful response by one of my favorite photographers, David duChemin. He began with a quote from JFK: “When written in Chinese the word crisis is composed of two characters. One represents danger, and the other represents opportunity.” This made me really stop and think. Perhaps if we quit mudding the waters with our frantic baling and arguing over who is responsible for this mess we find ourselves in and pause long enough for the water to settle and clear—if we settle ourselves into the quiet and let go of our fear—stop scrolling the newsfeed, and listening to every pundit trying to figure out how to get us back to the way things were, we might be able to see, between the hard, dark rocks that iridescent glimmer of light—the opportunities that this crisis opens up for us individually and as a society.

The greatest lesson I have learned in my studies of Buddhism is detachment. Practicing it during past personal crises has helped me to calm the roiling waters of my mind and see with clarity the light of opportunity shining between the rock and the hard place.

So I’m going to stop my frantic attempts to bale—stop the fretting and worrying over all the things I have no control over anyway and step out of the boat. I’m going to wade ashore and sit quietly, looking out at the lake. Figure out where I am and where I really want to be. No longer to go with the flow or to try to get back in the current that has so often swept me away, but to calm my mind, detach, be still long enough that I can see the light playing between the rocks.

DuChemin finishes by saying: “More than any of the things above, this is an opportunity to give more and to be more: more attentive, more creative, more generous, more wide awake. It’s an opportunity to rise to the daily challenge of the new normal, and to fight to make that normal better and kinder for all. . .We might be in this for a while and I don’t want to look back once we emerge from it and wonder why I wasted weeks or months of time and focus I’ve never had before.”

Scrolling our newsfeed

unseen, spring awakens and

flickers laugh at us

A wind storm ripped through the valley a few days ago and sometime between the midnight howling of the coyotes and the early morning trill and thrum of redwing blackbirds I heard the crack and whoosh of falling trees. The next day I found, stretched through the middle of the heron rookery a newly wind- felled cottonwood and there on the ground, the huge tangly branched nest with broken eggs, the blue shells still spattered with yellow yolk.

Over the last two weeks the herons have been returning to the rookery and are busy building and repairing nests, the old established couples reuniting and reclaiming their places, the young males hopefully proffering a particularly fine twig to perspective females. There is much flying about, loud grumblings and neck stretching threats when rivals fly too close to an already claimed nest space. One or another flies out to hunt the nearby field for emerging ground squirrels or fish from the ice cleared river. Meanwhile, back at the rookery long necks stretch and contort to preen feathers into place. Then a sudden cacophony as a red tail hawk flies through on a recon mission, razor sharp heron beaks clacking warnings at the interloper.

As the sun sinks lower more hunters return. A male settles onto a branch above a nest. The female stands and stretches her neck up to clack beaks. Loud gurgles and harsh cooing intensifies, wings flap and the male hovers over the female. The mating is quick, then both smooth their ruffled feathers, settle side by side into the nest and watch the darkening night sky.

The windstorm of the coronavirus pandemic has blown through our world, toppling all our well laid plans and breaking open our day to day lives. In other crises–fire, hurricane, earthquake or flood, even 9/11, we have rushed headlong into getting things “back to the way they were.” But this time we may not be able to get “back to the way things were.” And perhaps we shouldn’t even try., This crisis has really put the flaws in the way things are into sharp relief. I’m hoping, given the time we have now for reflection, that we can, as individuals, businesses and a country, use this hiatus to really do some soul searching and re-imagine different priorities and a different lifestyle. My mother talked about the depression and how that changed everything–made people more self-sufficient, more frugal, put the emphasis back on relationships and community and being more generous and empathetic to others, even when people had so little to share. She was horrified to see how our society changed in the prosperity that followed the war–how we became, not citizens, but consumers. How we stopped making do and being grateful for what we had, but became unhappy and dissatisfied always wanting more and more. And she was so disheartened when, on 9/11 the rallying cry was to go out and go shopping. I never really took her complaints seriously until now. I can see how so much of my life is consumed with consuming, and how, my generation feels so entitled.

The tree has fallen, our nest lies shattered on the ground. Let’s look to a different, stronger tree in which to rebuild and lay out our priorities.

Somewhere in the woods

piercing scream of hawk caught hare

presaged in his track

There is nothing left of the carcass. The bones have sunk down into the muddy weeds or have been scattered about the field and the tawny hair of the deer blends so perfectly with the winter dried grasses that it is invisible. It took but three days for the road killed doe to be reduced to a memory. But for those three days it was a scene of endless drama. I glimpsed the lump of her body first in the early morning. By the time I drove past a few hours later the magpies had found her and it looked as if the field were aflutter with giant iridescent blue and white butterflies. Next came the ravens and I watched as a hierarchy of corvids established themselves—a few feeding while the others stood apart awaiting their turn. Meanwhile the magpies snuck in, snatching pieces of red meat while avoiding the snapping black beaks of the ravens who chased them off. Cars rushed past on their way to town oblivious of the drama playing out in the field.

By evening a bald eagle had arrived, his white head I first mistook as a patch of leftover snow. The eagle asserted his primacy on the carcass and now the ravens were the ones who had to try to sneak a morsel. The magpies flew overhead circling, but giving up on getting any closer. The eagle, though white headed, still sported a few streaks of brown on the back of his neck, so he was young.

Then the gang of immature eagles arrived, still in their brown plumage, four in all and they surrounded the carcass, pushing the solitary older eagle off, then taking turns feeding on the dwindling meat. For the rest of the second day, and part of the third, the young eagles dominated, the white headed elder picking at a bone some distance away and the ravens and magpies trying an occasional end run around a feeding raptor. By that evening, the ravens and magpies were finishing off whatever remained.

Watching all this I was acutely aware of the program I had just seen the week before at the Montana Natural History Center. The eagle researcher from the MPG ranch, which lies just south of here, described their studies of migration patterns and their capture and banding of the eagles who frequent the ranch. I peered through my binoculars trying to see if any of these eagle were tagged, but none appeared to be. I was also acutely aware of what the researcher had said about the alarming amount of lead they found in so many of the eagle’s blood.

With climate change and facing the next great extinction, it is easy to feel helpless in the face of these global problems. But here was a one small contribution toward preservation that anyone who hunts can take. While this particular deer had been hit by a car and not shot, the quick and efficient way the birds had eliminated the dead doe was a clear illustration of how these scavengers, feeding on carcasses and gut piles left by hunters using lead ammunition can be poisoned. A simple switch to copper bullets could make a huge difference in the lead contamination in the environment and seems a no-brainer for anyone who cares about the future.